Dr. Rob Garofalo, MD, International Expert On The Health Needs Of Marginalized Youth

When it comes to treating the health needs of marginalized youth, many doctors and clinicians, unfortunately, don’t have the skillset to relate with them. However, Dr. Rob Garofalo is different. He has experienced many challenges in his life, including being HIV positive, experiencing a violent attack, and surviving cancer. Dr. Garofalo is a pediatrician, researcher, activist, author, ally, and leader. He also founded the charity Fred Says, which raises money for HIV-positive youth. Join J.R. Lowry as he talks to Dr. Garofalo about how being open about his own issued allowed him to take his practice and his broader work to another level. Tune in and find the inspiration to be your authentic self!

—

Listen to the podcast here

Dr. Rob Garofalo, MD, International Expert On The Health Needs Of Marginalized Youth

On A Career Journey Dedicated To Addressing LGBT Health Issues, Adolescent Sexuality, And HIV Clinical Care And Prevention

I have the honor of welcoming my longtime friend, Dr. Rob Garofalo, to the show. Rob and I both lived in the same dorm during our freshman year at Duke. He has gone on to do a number of great things since then, dedicating his life’s work to addressing adolescent health issues, focusing in particular on HIV-positive and LGBTQ+ youth. Dr. Rob is a Division Chief of The Potocsnak Family Division of Adolescent and Young Adult Medicine at Lurie Children’s Hospital in Chicago.

He is also the Director of Adolescent HIV Services and the Research Center for Gender, Sexuality and HIV Prevention. He is an Editor-in-Chief of the Transgender Health Journal, Professor of Pediatrics and Preventive Medicine at Northwestern University’s Feinberg School of Medicine and the Founder of a 501(c)(3) charity called Fred Says that raises money for HIV positive youth.

Rob has become an international expert and a leading voice on LGBT health issues, adolescent sexuality, and HIV clinical care and prevention. He has spoken around the world on these topics. He is a longtime board member of several medical associations, including being a past president of the Gay and Lesbian Medical Association. He has been the principal investigator and a co-investigator on a number of National Institute of Health and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention-funded research grants and served on a committee of the National Academy of Sciences.

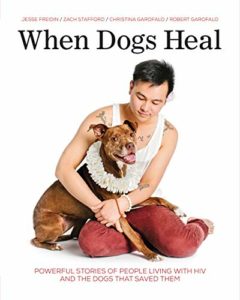

He has won numerous awards for his work, including the Lorrie Lane Brenneman Lifetime Achievement Award. He is a multi-year AIDSRide fundraiser. He has been quoted in Time Magazine, featured in People Magazine, and appeared on Dr. Oz. He has written for the HuffPost. He even authored a book called When Dogs Heal and appeared in a movie that was screened at the Cannes Film Festival, which he attended that year.

In addition to his undergraduate degree from Duke, Rob earned his MD from New York University and a Master’s in Public Health from Harvard University. Rob is a fitting guest for this particular episode which will drop on Patriot’s Day in Massachusetts. I will be in Massachusetts in Boston, running the Boston Marathon and raising money for the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute.

Dr. Rob is a cancer survivor himself. He has used that experience, among many other things, to fuel and help bring purpose to the work that he does. I hope you will consider contributing to cancer research in whatever form, to whatever institution, and will also consider contributing to some of the great work that Dr. Rob is doing, particularly through his charity, Fred Says.

—

Rob, welcome. It is a privilege to spend this time with you. Take us back to the beginning. When did you first decide that you wanted to go into medicine?

When we were in college, I decided that I wanted to pursue becoming a doctor. I did not decide on what area of medicine until I was doing it. I decided to become a pediatrician when I was in medical school, when they make you go through all the rotations, like internal medicine, psychiatry, and OB-GYN. While I loved all of them, pediatrics was the one that I felt most at peace with. It was not the one that thrilled me. It was the one where I found the most peace and tranquility. It was also the discipline where I felt like I was investing in someone’s future, rather than preventing or treating diseases that had been built up over a lifetime of bad eating or bad habits and now I had to fix it.

With children, I had a chance to [help them] from the ground up, as they say. I decided during my pediatrics training that I had a real passion for dealing with adolescents and young adults, which is an often forgotten group in pediatrics. Even within that, I decided to do HIV work in part because I wanted to work with marginalized populations of kids.

That is who I started seeing back in the ‘90s. My career has taken lots of pivots, most recently to care for transgender children, gender non-conforming, or gender-expansive children and adolescents. All of these communities that I have the good fortune of devoting my career to have been blessings. I learn as much from them as they do from me, if not more so.

Dr. Rob Garofalo: You already put enough pressure on yourself to succeed. You don’t need added pressure from an institution. Break out on your own and forge your own destiny.

You talked about peace. What was it that made that an important consideration for you in choosing pediatrics?

Someone had given me that advice. Honestly, I don’t even know who. Someone told me in my medical training, “Don’t choose the discipline that wows you. When you do your surgical rotation, there are going to be many amazing things that you have never seen before. Keep reminding yourself that the 100th time you have done a gallbladder operation, it is not going to be as exciting as the first time you see one. Don’t be wowed by a particular procedure or a thing. Try to look at each rotation [and determine] which one gives you a sense of inner peace and inner worth.” For me, that was pediatrics from the beginning. It was not like I got a lot of support for that. It is the lowest paid medical specialty.

I was a good medical student. They were encouraging me to do something a little bit more sexy, like radiology, anesthesia, or surgery but those things never appealed to me. I am a klutz, so I could not possibly do surgery. Pediatrics was something that always seemed a good fit for me. You know this, both my parents are teachers. There is something about that multi-generational type thing. My parents clearly did not want me to become a teacher for any one of a number of reasons. Something about medicine and doing pediatrics felt like it honored them and many of the values that they instilled in me.

After medical school, you spent some time both in Boston and Philadelphia. What were those early years of practicing medicine like for you?

I did my residency in Philadelphia. That was – grind it out and get through the days and the weekends and 24-hour calls. I basically did my fellowship in my early training in Boston. I got my training at Harvard but I worked at a community-based site called the Sidney Borum Jr. Health Center. They gave me the roots for the rest of my career because it was an unconventional community-based clinic that was devoted to deconstructing the hierarchy of medicine and what it meant to provide services both to and within communities. I was funded initially by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. I was one of their first doctors but it was a very unconventional model, which I flourished in. It was about making connections with young people who felt disempowered and disenfranchised from the medical community.

That, for me, was like waving a red flag to a bull. I loved that aspect of it. I ultimately did not like the Harvard culture much. I looked forward to leaving that environment in part. It is an amazing place. I put enough pressure on myself to succeed that I didn’t feel like I needed the added pressure being put on by an institution to succeed. I ended up moving to Chicago in part because I could break out on my own.

There was nothing here at that time that I moved here. It was an opportunity not to be on a very tall totem pole, but I got to forge my own destiny. In hindsight, someone asked me, “What is your favorite thing about your job?” I was like, “I get to create.” That is probably the skillset that I feel I enjoy and tap into the most,fds when I get to build things or create.

When you were out in Boston, you got your Master’s in Public Health from Harvard. Why did you decide to do that on top of getting your medical degree? How did that complement the skillset that you already had?

For me, I always looked at an MPH as a type of calling card to scream out to people like, “I am a doctor but I also care about public health in a broader sense.” Doctors can sometimes get a bad rap. For me, an MPH was the ticket I needed to make sure, in my mind, that people knew that I had a broader outlook on public health and communities. Whether or not I gained those skills when I was at Harvard, I am not sure. It was an amazing place. The quirkiness of the funding for my MPH came through the Maternal Child Health Bureau. I had to get my MPH in Childhood Development or whatever the track was. It was essentially what I was doing day in and day out.

If I had to advise people who are going through these things, if you are going to get another degree like I did here, make sure you are adding skills, not just three letters after your name. I wish I had been more targeted in the skills that I had obtained there, either around epidemiology, statistical methods, or something that would have served me a bit better in terms of my academic career, which has clearly been fine but it was not my MPH that expanded my skillset, mostly because of the way that the funding was obtained.

If you're going to get another degree, make sure you're adding skills, not just three letters after your name. Share on XYou’ve spent a lot of time in Chicago, not just practicing but also being a director and division chief in a large hospital. What is that like to have a dual role of trying to practice medicine every day but also having to manage a group of people and all the administrative stuff?

If you ever would have told me many years ago that this would be the career that I would have, I would have just giggled. I never thought that I would be working with LGBTQ youth, HIV or trans kids. These were not even disciplines back then but it was something that was important to me. I started off my career as a clinician and then I realized early on that the biggest deficit in every budget I ever created was my own salary. I have to figure out creative ways of funding myself. I became a researcher. If there is one thing that I am probably known for now in my career, because I have been generously funded by the NIH over the years, it is that I am an academic researcher.

That also makes me giggle because it is the hat I probably wear with the most discomfort. In my mind, I am still this clinician pediatrician who cares for kids and builds programs. The admin piece and the research piece, which are now, in some ways, the lion’s share of my responsibilities, are probably the skills that I never saw coming, never thought I had, and never was taught. You learn them on the fly. I love my job. I have been able to build it with incredible gratitude for the philanthropic partners who have allowed me to get from point A to point B. Let’s call it what it is. Without philanthropic partners, it could have never happened.

I have been able to build a division and a team around the quirky clinical and academic interests that are important to me. I now have this robust division of adolescent medicine that has its roots in the history of LGBTQ youth, trans kids, and HIV. That is unheard of. It was a research team that then added clinical pieces to it because I was doing so much NIH-funded research. Somedays, I go to work, I look out the window, I take a breath and I am like, “How the F did this happen?” I love it and I am pretty good at it, if I am honest. We now have a team of about 100 people.

I have fifteen multi-disciplinary faculty. We have an important signature program in substance use and HIV. In part, so much of it is tied to my own personal identity as a gay man. I was not even out in college. Much of my own personal evolution and my own comfort in becoming confident in myself – I have been able to express that in my own career. I am HIV positive. Even the work that I do in the HIV field has been driven by a passion that is an odd mix of my career and academic proclivities and my own personal life and personal skills.

That even includes our substance use program because I am also in recovery. All those things, my HIV, the recovery, all that bag of bull crap, have made me a lot of things at times, maybe a little erratic or crazy, but it has also made me effective because these are kids and families. It is not esoteric to me. These are young people, conditions, and families who I deeply want to help. That has always been the thing that weirds people out in some ways in academia but has also been my superpower.

Academics aren’t generally authentic. Doctors do not bring to the table their vulnerabilities. Even at my job, over the years, I have become comfortable with who I am. Initially, they were like, “What have we gotten ourselves into here?” Now that I’ve been successful, that success has allowed me to talk more openly about those things. It is a positive feedback loop.

When you are working with these kids and their families, you can relate completely to what they’re going through. You have been there in more ways than one.

I remember the first time I talked to donors about my history of addiction and recovery. I watched the poor guy from my hospital foundation turn to ash and gray. He was like, “What is this guy talking about?” I am pretty good about reading a room. I am not going to bring that up with everybody. When I am making a connection with a family who’s lost their son from opiate addiction, I know what that struggle is. I do not necessarily know about opiates because that was not my thing but I know how hard the struggle of addiction is and how hard it is to stay in recovery.

Over the years, I haven’t had any difficulty talking about it. For me, the boundaries are very clear. For some, they get nervous that I am going to cross some boundary. For me, it is not hard to maintain those boundaries. Sometimes even on social media, people are like, “He is going to overshare.” Social media is a carefully orchestrated press release.

Dr. Rob Garofalo: Academics aren’t generally authentic. Doctors don’t bring their vulnerabilities to the table. It helps to be able to relate to your young patients who have conditions like HIV.

You obviously use Facebook in a very different way than a lot of people do. At the same time, there is a very strong following around Dr. Rob Garofalo. You touch a lot of people’s lives in the way that you open up on Facebook. It comes back to it being your identity. You’ve become more comfortable with it. It is intertwined with how you practice and everything.

It is not like I want to cultivate a following. I am just being my natural self. The work that I am doing is meaningful and important to me. The funny thing is I never used social media until I formed the charity that I did with my dog, which was after I had experienced a traumatic event and I had cancer and HIV. I finally found my life again and wanted to celebrate that right with this crazy dog who was cute. I started this random nonprofit charity, rode a bike, washed dogs, and did dog daycare to raise enough money to keep my website going early on.

I remember when I told my hospital that I was going to start an HIV charity with my dog. They were like, “What?” I was like, “You watch me.” It’s sad because we have raised $300,000 over the past few years but when Fred died, we had such a following. We had an angel donor that donated over $500,000 to the charity so that we could give back to the community, with a note that said, “You and Fred have only just begun to change the world.” That now do I not only get to do the work in these communities, but actually get to fund good people to do the work as well, is mind-blowing to me.

Fred has passed away but his legacy lives on in such a positive way. It’s pretty amazing. I know how important he was to you and digging you out of the depths of those dark days.

In that charity, I also found my own voice, which I did not have in academic medicine. I was always a little unconstrained, because I am the most unconstrained academic, but I wanted something that was mine and personal. The goofier I made it, the more successful we were. I made a Men of Fred calendar for one year. I wrote a book, When Dogs Heal, which was in People magazine. It was pretty remarkable. Again, I think I have been able to tap into something that is not unique to me, like the power of people’s pets, especially in this pandemic.

I am so blessed. As someone who’s had cancer and HIV, been assaulted, and had a lot of shitty things happen in his life, I am also incredibly blessed. One of the biggest challenges for me and my life has been reconciling that two complete opposites can also equally be true. All those shitty things happened, and they are real, but I can also acknowledge that I am privileged and incredibly blessed to do what I am doing.

You are a remarkable example of somebody who took a lot of bad things that have happened over the years and used them to fuel you and give you purpose in what you do day-to-day. Not very many people can do that.

It was the dog, I’m telling you. I was not going to make it to another day and then I got this dog. He had no patience for me being in my head. He needed me to be present. For him, I got through those early days. That is why, in some ways, I started the charity. When I did find my footing again, I felt so blessed that I knew I had to give something back. There have been multiple times over the past few years where my day job has been super busy. There have been times when I am like, “I don’t know. Should I really be running a nonprofit charity?” I don’t have time but it brings me a lot of joy. Now with these angel donors, and a number of people supported us after Fred died, we get to be angel donors to people. It is a remarkable world.

The other thing you said, it is also important, this idea that you have to operate within boundaries in your day job but you have found an outlet in Fred Says that you can make your own. For me, a little bit of why I wanted to do this show was for the same reason. I’m fascinated by people’s career stories. This is a way for me to do it that is attached to me and not necessarily to what I am doing in my day job.

I asked Lurie Children’s…I have nothing but praise for my employers because they have put up with a lot for me. I have done well by them. In the early days, I asked them to take over the charity. I said, “I’ve got this idea. I want to raise money for your program.” They thought I was batshit crazy. They were like, “What are you talking about?” I’m grateful that they said no back then because I was so pissed that I was like, “I’m going to show them. I’m going to form this charity and make something of it.” Believe me. The charity also continues to fund some of the work that I am doing at Lurie’s. I am grateful that they said no and forced me to do this from the ground up, as I otherwise probably wouldn’t have done it.

My social media is like a carefully orchestrated press release. Share on XIt’s more fuel for the fire.

“I wanted to write this book, When Dogs Heal.” People were like, “What? You’re going to write a book about people living with HIV that have dogs?” I was like, “Yeah.” It worked and I met amazing people writing that book. I got to work with my niece. She was born right when we graduated from college. It enabled me to form a connection with my niece because she ended up being one of the main writers in the book. That was also super important to me that she got a sense of not just me as a person but also my life and my career in a way by participating in the book. You can’t make this shit up. It’s super meaningful.

You were practicing, running your center, doing research, and running your charity. We haven’t even talked about the fact that you were also teaching at Northwestern.

I do not do a ton of teaching. I have been really fortunate to be generously funded and to have key philanthropic partners from the community over the years who trust me. That is something that I take incredibly seriously. If you donate $10 or $1 million, I am a good steward of philanthropy, and I take it seriously. It’s important to me. I do all those things still. Now I am doing international work, which has been the other privilege that has been meaningful to me.

I have been doing work in Nigeria lately that feels like it is some of the most important work of my career, because we are working with criminalized populations of gay men, getting them access to HIV testing, and connecting them to care. I designed a medication adherence intervention. Now we are enrolling HIV positive adolescents who struggle with their medication adherence. I can take some of the stuff that I have done here in the US, where the HIV epidemic is not over, but it is far less than what is going on in Nigeria, and be able to do this work with an incredible team.

How did that come about?

I was sitting on a plane going to the International AIDS Conference. I was sitting next to this guy. My boss walks down the aisle and is like, “Two of my favorite people sitting next to one another.” I didn’t even know who I was sitting next to. It turned out that I was sitting next to Babafemi Taiwo, who is the Head of Infectious Diseases at Northwestern, who I’d never met. He is Nigerian. On this flight to the International AIDS Conference, he was telling me about the work that he has done around HIV in Nigeria. He was imploring me to come to give a lecture. He said, “Working with gay men there is so stigmatized. I’ve never been able to get anyone to have an interest in doing it. Would you come and give a lecture?”

I said, “I’ll give a lecture.” My favorite part of this story is that the whole time I was like, “I do not want to give this lecture. I do not want to go to Nigeria. They’re going to throw me in jail.” If I am going to do academic tourism, I want to go somewhere where there is a waterfall, a little café, and a beach somewhere, where I can hang out. Not somewhere where they’re going to throw me in jail. I thought I am doing one lecture and I am out. When I went there, [Babafemi] was super smart. He convened this group of HIV positive young men, mostly young gay men, to talk to me about their lives and their experiences. It was life-changing to hear these young men describe their lives, conditions, and challenges in ways that we can’t even imagine here.

The next day, these young men showed up at my lecture. They had never met another HIV positive gay man who was a doctor. I left that lecture and I said, “I am not sure how or when, but I am going to come back. I’m going to figure out a way to help.” Babafemi and I partnered. We wrote this grant to the NIH called iCare Nigeria. I’m not somebody who hasn’t done meaningful things in my career and yet I think it is one of the most meaningful things I have ever been a part of. My partnership with him and with the team that we have in Nigeria is very important to me even though it is still not an easy place to go, and it is not easy to be a gay man there. I’m still looking for my waterfall, my beach, and my safari, but it’s not going to be there.

You have become an expert and a leading voice on issues faced by HIV positive and LGBTQ youth. Maybe this is a hard question to answer precisely but what factors led to you becoming so recognized in this space?

Dr. Rob Garofalo: Make it so that whenever you leave a certain community, they are set up for success. It’s not about keeping your legacy, but it’s the legacy of giving back to the community in some way.

I have to say it’s a combination of things. One, I’m like J. Lo. I’m like a triple threat. I do clinical work. I do research. I am not afraid to be authentically me. Those three things together have proven to be pretty important. I don’t want to minimize any of them. I became a clinical expert in an area and then, in some ways, I became an academic, where I have done what I was supposed to do, which was publish a lot of papers and get grants.

Increasingly, by doing those two things, it freed me up to also find my own voice. If I was a so-so clinician and a mediocre academic, I might not feel so comfortable being open about my own struggles with HIV or my struggles with addiction and recovery. It is because I have these traditional markers of success nobody can take away that frees me up. It is like this positive feedback loop. Each one helps the other ones get better. Now it’s too late. The genie is out of the bottle. Honestly, I am willing to put myself out there. I also have the credentials to back myself up.

In HIV and addiction, there are very few doctors who are willing to talk about either of those two things as their own personal experiences. I don’t quite get it. Addiction, I would say, is still the ultimate taboo. I get it because it could impact patient care and things like that, although my addiction never did. We’re not perfect. What is this fallacy that doctors have to be perfect beings? I’ve got news for you, none of us are perfect. It’s okay. Again, I feel safe doing it because people can’t take away the other things that I’ve done.

This whole idea of vulnerability…Brené Brown and others have made it a much more acceptable thing to talk about. Leaders in a lot of different situations are more willing to show their own vulnerability. The medical profession is probably one of the last holdouts.

It’s risky on some level but perhaps it’s also because I am a gay man. I know the risks of secrecy. Concealment has always been a harbinger of bad things in my life. Openness and authentically being me have always been a recipe for good. I know that there are people out there who I am going to rub the wrong way and who are going to be like, “What?” I don’t care. There are enough people that are going to hear my voice and feel like I’m talking from my heart and soul. Doctors are not trained to do that necessarily.

I have a doctor who has gone through a cancer battle and her husband has had early onset dementia. It’s hard for her to talk about it. She is in that patient-doctor mode. I am at a point in my life where I am in person-to-person mode.

Maybe it was getting cancer at a young age. That was the first domino that fell for me. I was diagnosed with cancer when I was 39. That experience made me look at the world through a different lens and be grateful for each day I was given, even though some of the days that followed were dark days. I’m trying to ride the waves of life as supposed to being engulfed by them, even with my addiction, which I think was probably the biggest struggle of all of them for me. That also has been a battle of perseverance. It has not been easy. I have relapsed a number of times, usually short relapses, thank God. I get right back at it. I don’t take any day for granted because it is a vicious disease.

It’s something you always have to guard against.

My last relapse, which I have talked openly about, was when my dog died. I was simply not equipped to handle how I felt after that. I could either feel shame about that or acknowledge it, get back on the horse, and learn from it, but then also use my experience to shine a light on this disease or process hopefully. Maybe someone else down the line will understand that a bit better or won’t have some of the struggles that I’ve had.

That is one of the mindsets that I tend to have about life, which is to share my experiences, because I sure as hell know that I am not unique in them. Sometimes even with cancer and addiction, I think like, “I have a job, health insurance, and a family that loves me. I have all these amazing things and yet they were crippling.” What’s it like for people out there that have to deal with these things who don’t have a job, insurance, or a loving family?

Concealment has always been a harbinger of bad things, while openness has always been a recipe for good. Share on XOr live in a country where being gay alone is criminal.

That’s how I have lived my life, which is to be very aware of the impact that I can have by being honest as opposed to being dishonest. It’s not about lying per se but it would be about sins of omission to some extent.

We’ve talked about this a little bit. As you look back over the years, how much would you say that your career progression has been a series of intentional moves? How much would you say it has been a series of opportunistic events?

I would put 85% to 90% in the opportunistic event category. I have had a game plan but I have always been someone that looks in the moment at the opportunity that is in front of me and makes a decision. The question that would perturb me the most in a job interview, which I would never know how to answer, was, “Where do you see yourself five years from now?” God only knows.

I have gone through some real soul searching where I have been actively recruited for a range of pretty high-powered jobs. It has been ego-stroking in some ways but it has also been a good process for me to take a breath and realize I don’t have to keep aspiring to want to be more or do more. I am in the lane right now that I want to be, where I want to be, working with the people I want to be, and doing the work that I want to do.

I do think, in some shape or form, that I will just keep expanding what I am doing. That has been in the recent past for me, because before then I was like, “What’s next for me? Should I be a dean in a school of public health, trying to climb the academic ladder, just one more rung? I could do it but I am doing what I want to do.” Going back to that notion of peace, there is some peace that I have found over the past, in knowing that this is the space that I need to be in.

You’ve said that you created that center pretty much from scratch. You’ve built a situation over the years where you’ve got a ton of autonomy and you have such a strong sense of purpose in working with these kids and their families. If you’re a dean, you’re going to deal with politics.

As a department chair, you have to be the ultimate politician. The other thing, and we haven’t touched upon this, but I’ve been focused on legacy. Not legacy like, “This is what Dr. Rob Garofalo did,” but whenever I leave, I want to make sure that these communities are set up, not because it is about me. It’s not my legacy but it’s the legacy of giving back to the community in some way. I have been focused on that these past couple of years, even with my philanthropic partners.

I’ve got about ten more years in me, ideally, God willing. How do I make sure over these next ten years that when I am done, whoever comes and takes my place, they are set? I don’t want to say that it’s super unusual but it’s somehow unusual. A lot of people look out for their own careers but I’ve been driven by the work in the communities that I care for as much as by the rest of it.

You’ve talked a little bit about the strengths that you have tapped into along the way. What have you had to develop over the years and how did you do that?

Let’s start with the negatives. I reside in anxiety. I’m a super anxious guy. Anyone that works with me knows it. I’ve had to learn to be resilient, however you define that. I’ve also had to learn to laugh at myself along the way. You can’t take yourself seriously and still want to have the impact that I want to have and do the work that I want to do. Those would be two, a sense of humor and the ability to laugh at myself and ride the waves.

One that I am still working on is not taking things too personally. The last couple of years for me, in particular, have been difficult, especially as a White man in a position of power and privilege, which I have. The programs and the center that I built were built with a focus on sexual equity, an equity lens focused on sexual and gender minorities without as much of a focus on racial equity.

That’s the truth. In my research and the programs, they were about HIV positive youth who care for Black people but they were not centered on the experiences of Black or Brown people. It’s another area where, a few years ago, during the social unrest that we all experienced, I came up with a decision that I’d have to look at the work that I’m doing and that we are doing through that interdisciplinary and racial equity lens.

If I can’t, then I should retire and move on and be like, “I’ve done really good things. Now it’s off to somewhere else.” I am staying in this space in part because I’m excited about self-improvement in this space and doing this work imperfectly but better. Another skill is learning how to be comfortable with being imperfect.

It goes back to what we talked about a little bit ago about vulnerability and being comfortable in your own skin that everybody, to some degree, develops over the years, some more than others.

The recovery journey, as crazy as it seems, has been, in some ways, the most enlightening for me, because what you learn in addiction recovery is that there is no shame. The only shame is in giving up. The only shame is in saying, “I can’t fight this battle anymore.” Continuing to show up, even when it’s ugly and even when you are having bad days because you know that maybe tomorrow is going to be a little bit of a better day…I don’t even know whether you would call it a skill, but that skill, whatever we choose to call it, is something that I tap into a lot professionally. You know this. There are good days and bad days.

Some of the bad days are really bad, but then the next week, they get better. Particularly around mentorship, I am enjoying mentorship these days. I am focused on mentoring my junior faculty. In academic medicine, there is this staunchly held belief that as a doctor you can be a good clinician or you can be a good researcher but you can’t be both. You’ve got to pick one. Pick your lane and you can only be good at one of them. That’s a bag of bullshit. I don;t believe in that. The two have been intertwined for me. The only reason why I am a good researcher is because I am also a good clinician.

Many of the skills that I have learned in research have also helped make me a good clinician. I believe in a clinical research model that’s not the conventional wisdom in academic medicine. They encourage you in many ways to do one or the other and never protect your time enough in one or the other to do the alternative well. I believe that the two are symbiotic.

You’ve helped a ton of people in your career in lots of different ways. Apart from the philanthropists that have funded some of the work you’ve done, who has helped you along the way?

Many people. It would start with the philanthropists, like Jennifer Pritzker. One day, she will get credit for redefining the field of gender medicine for children. She gave us a ticket to be able to build programs in a way that we could have never done [on our own]. I know we glossed over the philanthropists but the people in the community that has supported our work and said that these young people matter, they’re heroes to me.

Learn to have a sense of humor, and stop taking things too personally. Share on XI have benefited from terrific mentors over the years. In some ways, that’s why I take mentorship seriously. When I wrote my first research grant at Lurie Children’s, I wrote an internal award to Lurie Children’s and submitted it, and I got this scathing review. It was so unproductive that I was pissed off.

In the review, it was like, “This idea of Dr. Garofalo is so stupid. He should learn from the smart work that Jerry Dannenberg does.” I googled her. She was at a university across town at the University of Illinois-Chicago. I looked at her research and I was like, “That’s not any better than mine.” I called her. She didn’t know anything about the populations I cared about but I was like, “Would you help me? Can you help me understand what is wrong with this?” She was like, “This is good. It’s just not packaged right.” She became a mentor to me.

Ram Yogev, my clinical mentor in HIV, cared for people deeply and taught me what it means to be a human and a clinician. Lisa Kuhns has been like my right-hand person for many years and has endured so many ups and downs related to my own health, addiction, and recovery. She has been not just a friend but a colleague, a mentee, and a mentor. Mentorship is so bi-directional. I can’t even imagine doing the work that we do without her.

There are people like Tom Shanley, who’s the President of my hospital, who I think early on realized that in giving me space to succeed, he succeeds. That’s not always true in leaders. They don’t want to get in your [corner]. Tom, who I’ve known for many years, gave me wings because he knew that if I was flying, he would also benefit from that and so would the institution. None of them have called themselves mentors, but I have found mentorship in lots of different spaces.

Any final thoughts you want to share before we wrap?

No. I’ve never actually talked about my career like this. It’s interesting. I would love to interview you back because I would love to hear a little bit more about what you’re doing. I feel like this has been in one direction. I hope we take the opportunity to connect and have a different conversation. I appreciate the interest in my career trajectory in part because I think it has been nontraditional in a lot of ways.

That’s where groundbreaking stuff happens.

I go to work every day, and I am blown away by what I get to do, where I get to do it, and who I get to do it with. You can’t ask for better than that. It’s all good. I appreciate the opportunity to chat.

It’s been great. I appreciate it as well. You have an amazing story in many different ways. You have done an amazing job of tapping into all the things that have happened to you and used them to drive you every day. Thank you, Rob.

That wraps up this episode. I’d like to thank my guest, Dr. Rob Garofalo, for joining me and sharing his incredibly impressive career story and what he has learned along the way. Please consider contributing to cancer research in honor of Dana-Farber or any other institution that you would like to support. Also, consider contributing to Rob’s charity, Fred Says, which you can find online, that helps support work for HIV-positive youth. Thank you. Have a great day.

Important Links

- Lurie Children’s Hospital

- Transgender Health Journal

- Feinberg School of Medicine

- Fred Says

- Gay and Lesbian Medical Association

- When Dogs Heal

- International AIDS Conference

- Babafemi Taiwo

- Jennifer Pritzker

- Ram Yogev

- Lisa Kuhns

- Tom Shanley

- PathWise.io

About Rob Garofalo

Rob is an international expert and leading voice on LGBT health issues, adolescent sexuality, and HIV clinical care and prevention, and he has spoken around the world on these topics. He is a longtime board member of several medical organizations, including being a past President of the Gay and Lesbian Medical Association. He has been the principal investigator and a co-investigator on a number of National Institute of Health (NIH) and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) funded research grants and served on a committee of the National Academy of Sciences.

He has won numerous awards for his work, including the Lorrie Lane Brenneman Lifetime Achievement Award. He is a multi-year AIDS Ride fundraiser, has been quoted in Time Magazine, featured in People magazine, appeared on Dr. Oz, written for the HuffPost, authored a photo book called When Dogs Heal, and he even appeared in a movie that was screened at the Cannes Film Festival. In addition to his undergraduate degree from Duke, Rob earned his MD at New York University and a Master’s in Public Health from Harvard University.