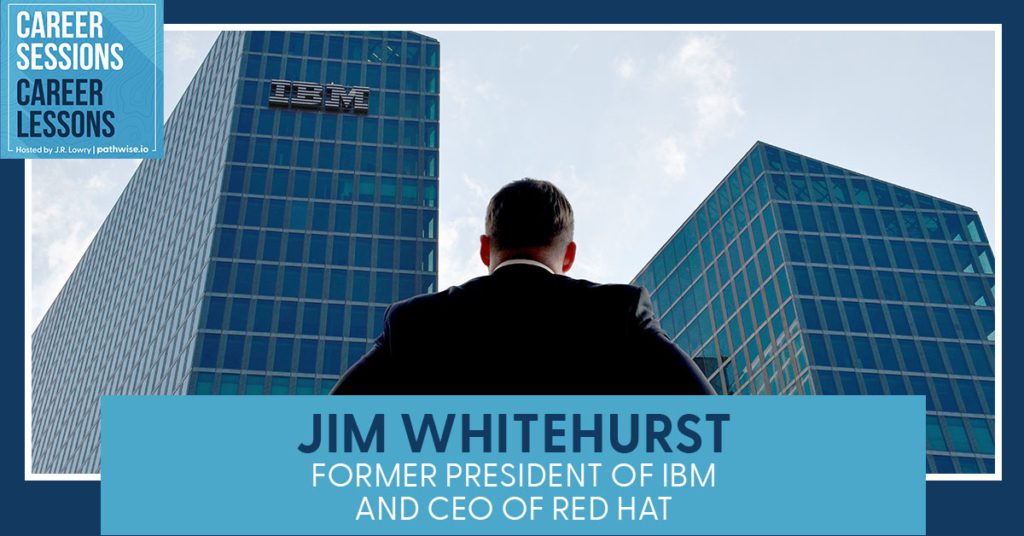

Jim Whitehurst, Former President Of IBM And CEO of Red Hat

In today’s fast-paced and ever-changing landscape, leaders know that it takes speed and agility for a company to succeed. Yet many are frustrated that their organizations aren’t moving fast enough to stay competitive. In this episode, J.R. Lowry talks to Jim Whitehurst, a Senior Advisor at IBM and Special Advisor to the private equity firm Silver Lake. Jim is the former President of IBM and Chairman and CEO of Red Hat, which IBM acquired in 2019. Before that, he was the Chief Operating Officer of Delta Air Lines. He began his career at Boston Consulting Group, where he rose to the level of partner before joining Delta in 2001. He is also the author of a book called The Open Organization: Igniting Passion and Performance, which the Harvard Business Review published in 2015. Jim shares his insights on effective leadership, employee motivation, and company culture. If your organization is struggling to adapt to the digital and social age, this episode is for you.

Watch the episode here

Listen to the podcast here

Jim Whitehurst, Former President Of IBM And CEO of Red Hat

On ‘Baptism By Fire’ At Delta Airlines, 10x Growth At Red Hat, And Integration Into IBM

I have the honor of welcoming Jim Whitehurst, whom I have known since we met back in the day as section mates at Harvard Business School. He is the former President of IBM and, prior to that, was the Chairman and CEO of Red Hat, which IBM acquired in 2019. Prior to taking over Red Hat, he was the Chief Operating Officer of Delta Airlines. He began his career at Boston Consulting Group, where he rose to the level of partner before joining Delta in 2001.

Jim is a Senior Advisor to IBM and a Special Advisor to the private equity firm Silver Lake. He is also on several boards of directors, including the board of United Airlines, and he is an advisory board member for Santander Bank. He’s a regular speaker at corporate and industry events, he has a TED Talk to his credit, and he spent a year producing a management and leadership video series called An Open Conversation With Jim.

He also wrote a book called The Open Organization: Igniting Passion and Performance, which was published by Harvard Business Review in 2015. He’s served as a member and Vice-Chairman of the North Carolina Economic Development Board. In 2014, he was selected as the recipient of the North Carolina State Park Scholarships Program William C Friday Award.

Jim is a graduate of Rice University, where he earned a Bachelor’s degree in Computer Science and Economics. During his undergraduate years, he spent time at the University of Erlangen Nuremberg in Germany and the London School of Economics. He earned his MBA from Harvard Business School. He and his wife live in New York City and have two college-aged children. Jim, welcome. It’s great to have you. I’m appreciative of your time.

Thanks for having me. It’s great to be here and reconnect with you.

It has been a long time since we’ve talked. You’ve had quite a career trajectory. In the intro, it talks about some careers taking off like rockets and others being more like the game of Chutes and Ladders. You are definitely more in the rocket category than the Chutes and Ladders category.

I usually start at the beginning but maybe we could start in the middle. You became CEO of Red Hat back in 2008. You were there for eleven years. You had come from Delta. How did you make that transition from an airline job into leading a tech company that was in its growth phase?

That was an amazing opportunity that came my way. I knew a board member from Red Hat who knew of me at Delta. He said, “We need to give this person a chance.” I have been screwing around with Linux for years, which is Red Hat’s main product. It is an avocation. When I first got the call, it came from a recruiter. It was public that I was leaving Delta at the time, and he said, “I’m not sure if you’ve ever heard of this company. They do this thing called Linux.” I said, “I know it. I use it at home. I know all about it.” I’m a little more techie than the average big company exec.

Most importantly, coming into any situation, I would tell people that one of the reasons I took the role is out a thesis of what I would do with it. I didn’t come in and say, “Thank you for the job. Now, let me go figure it out.” I spent time researching and had a sense of what I thought the company was doing well and the areas where we could do things differently and accelerate growth. Once you’ve got the thesis, then it’s about building a great team. They can go execute that because there are more things that I’m bad at than good at. One thing I think I’m good at is being self-aware enough to know what I’m good and bad at.

The beautiful thing when you have the latitude to hire your own team is you can hire for your weaknesses and build complementary strengths that, in total, can lead to everyone on the team being flawed, but the team itself not having a lot of flaws. We built a really good team and executed. It was a phenomenon of both honor and privilege but also an experience to be able to be a part of that.

Did you find that you had to change out a lot of the team when you got there?

I luckily didn’t but we had to make what I call tweaks. That’s one of the big decisions that people have to make, and there are different people with different styles around that. I know there are some people who come in and say, “I’m going to change out my team because I want the whole team to be loyal to me or to be who I’ve chosen, and I can craft it exactly right.” I cut my teeth in senior leadership at Delta when I was on a battlefield and was promoted to COO.

We were hurtling towards bankruptcy. I wasn’t spending time to go recruit people. Honestly, nobody in their right mind would have come to an airline in that situation. You had to take the existing team and work to craft it, use everyone’s strengths to craft it to excel as a team. We did fill in with a couple of people here and there.

It was more of that at Red Hat. We had a lot of the components of a strong team. I tried to take those and then made a couple of changes. I made a change in marketing and a couple of others. Seventy percent of the team was the same. I redirected them some and worked to build a team out of it. I tried to augment where there were weaknesses.

The normal human reaction to the level of stress is either let it eat you up or to say, 'I’m going to surf above it. Share on XEspecially coming in as the new leader to an industry that I wasn’t a part of, to me, it felt like continuity both in terms of a culture but also in experience. How was I going to know who a great product person was in software. I had never been in software. It made more sense to take the team and try to get the best out of them, observe where the gaps were, and then hire into those. I’m still a big fan of that.

I know I was forced into that at Delta, but I do oftentimes feel [leaders are] in a rush to say, “I want perfect people.” You end up changing people. Let’s be honest, at least I can say for myself, that I’m not that great at hiring. There’s a lot of data that says a lot of hiring decisions are mistakes. I would almost rather take what I know and work to optimize around that.

You’d been a COO in a huge company [Delta] prior to that, but what was different about becoming the CEO for you?

The thing you don’t appreciate is that when there’s no one behind the curtain, there is an enormous amount more focus and attention on you and stress associated with that. I thought, “I’ve had 80,000 people working for me at Delta. I ran a company through bankruptcy. I drove all the day-to-day. Therefore, I could be the CEO.” Red Hat, at the time, was a much smaller company. You get there on Day 1 and realize that if you walk in with a styrofoam cup, and luckily, I didn’t do that., people think you don’t care about the environment. All of these little things, everything you do, people are watching.

I remember this great story. One time my wife called me. She rarely calls me [when I’m in] meetings. With a group of people in the conference room, I said, “Excuse me for a second. My wife normally doesn’t call me. Let me step out real quick.” I stepped out to talk, came back, and thought nothing about it. Five years later, at a sales rewards club meeting, this is where the top salespeople come in, one of the women there came up to my wife and said, “I was about to resign from Red Hat five years ago because I was pregnant, and I wasn’t sure Red Hat would work [for me]. I was in a meeting with your husband, and you called. He stepped out to take the call. I thought, ‘If the CEO believes that it’s important enough, that family comes first, this is a company that I want to be a part of.’”

She’s wildly successful at Red Hat, but if I’d hit ignore, she wouldn’t be there. You don’t realize those things. On the flip side, after the Red Hat acquisition, I became President of IBM. I’m number two in a massive company. That was much less stressful because there’s somebody else behind the curtain and behind you. When there’s no one else there, and the decisions that you make can affect thousands of people’s lives, it’s different.

I remember at the Red Hat Halloween Party – the first version of Red Hat, Linux, came out on Halloween – that was our big holiday. Everybody brings their kids, and we do the trick-or-treating around the office. Every year, it’s a little bit stressful for me because I’m looking at all these kids running around with their parents working at Red Hat, thinking, “All these people rely on decisions that I’m making.”

It’s different being number 2 versus number 1. You read a lot of articles about these CEOs who would become completely arrogant and flame out because of hubris. They do stupid things. A lot of those folks, I now look back on and think, “There are two ways that some people deal with stress. One is you let it get to you, and you burn out. The other is you lock it away and say, ‘I’m going to convince myself that I’m right all the time and I’m all-knowing,'” and you become that arrogant [person].

A lot of [CEOs] probably weren’t that arrogant when they started, but it’s a normal human reaction to the level of stress you’re under. It’s either let it eat you up or to say, “I’m going to surf above it.” How do you get the balance right to stay humble, but not be eaten up by that stress? It is a tough trick. When I talked to other CEOs starting, getting that middle model right, where you don’t flame out because you burn out, but you don’t let hubris engulf you as a coping mechanism for all the stress, it’s tough. You’ve got to think hard about that.

I always have felt like people go down that arrogant path too because they are often surrounded by people who are afraid to tell them what they’re thinking, what they’re worried about, and what’s going on in their personal lives. They [the CEOs] don’t have the feedback that most people get. When you have a boss, at least you’re going to get feedback from your boss. When you’re a CEO, the chair of your board, if that’s an external person, or your other external board members, aren’t there every day. They aren’t seeing you every day. You lose that ability to get feedback unless you work really hard at it.

A couple of observations there. One is you are exactly right. You have to push really hard on people to say, “I want to know. I will see it as a favor to tell me this. This is not going to hurt me. I’ve got to know because if you don’t tell me, how am I going to know?” You have to beg for that. Frankly, having a good and stable family life is helpful. I always laugh and say, “I have a wife, a daughter, a mother, and a mother-in-law, and none of them is ever going to let my ego get too far.”

Being grounded with friends and family or something outside of work and then over-emphasizing how important feedback is internally with your reports is critical. I made almost all my executives do 360s, me included. I talked to the board to talk about my reports. That was anonymous. I think I did a good job of getting people to say, “I want feedback,” but then you’ve got it in a well-rounded package. If you don’t do that, it’s hard to know. The last time you ever know if your jokes are funny is the day before you are announced as a CEO.

You were CEO there [at Red Hat] for a long time leading up to when IBM acquired Red Hat. What do you look back and say, “These are the 2 or 3 things that I’m most proud of that we accomplished in my tenure?”

Jim Whitehurst: When you have the latitude to hire your own team, you can hire for your weaknesses and build complementary strengths. That can lead to everyone on the team being flawed, but the team itself not having a lot of flaws.

Without a doubt, number one, and when people ask me about the accomplishments at Red Hat, I always start off saying, “We were 1,500 people when I joined. We were 15,000 when we sold to IBM.” Building and creating a culture. As a team, I think we did a good job focusing on the culture. [You and I] talked [before recording] about The Open Organization, and we focused on that. Building and scaling that organization and the careers that got made around that is the thing, by far, I’m most proud of that we were able to accomplish. Without a doubt, number one is the people and their careers and scaling a culture.

Red Hat, not to get too far into the specifics of the company, is best known for open-source software. That means all the source code is free. You say, “How do you make money selling free software?” How you get people to pay for free software is an interesting trick. When we sold to IBM, we were the largest software transaction in history. I am proud of the fact that we took a disruptive model called open source and turned it into what was the largest software transaction in history.

VMware, assuming that deal closes, will be bigger, but there’s something about getting a traditional IT company to validate open source as a viable business model. It’s something I am extremely proud of as well. Those would be the biggest two. We went from being small to being an S&P 500 component, etc. Those were all great things, but it’s scaling the people and the team, those individuals, the senior team, and two levels down. I’m still great friends with all those people. [That and] the mark we made validating open source as a model are the two that come to mind immediately.

Red Hat led the way in the open-source movement. Now it’s mainstream.

It’s amazing to watch. We used to talk that Phase 1 of Red Hat was convincing people that open source was a viable alternative to traditional software, and Phase 2 was convincing people that it was the default choice. Certainly for infrastructure software, if you look at any of the major new things happening in AI, big data or DevOps and cloud, all of those things are open source. It did go from convincing people it was a viable alternative to literally being the default choice, at least for infrastructure. I’m proud of that because we played a significant role in making that happen.

You wrote a book about the open organization many years ago.

To be honest with you, I wish I had a do-over. Maybe in some spare time, I may do it, because that book was basically a little bit of my articulation of going from Delta [to Red Hat]. Delta is always on the list of most admired companies and all that. It’s easy to criticize because we’ve all had our bags lost and flights get canceled, but it is considered a well-run airline. I [went] to Red Hat, and for the first couple of months, I thought, “This place is chaos.” They have no idea what good management practices are. I’ve been brought in here to clean it up. Luckily, I didn’t know enough about software to start cleaning it up.

I was out meeting customers and trying to get my bearings. I realized over time that the Red Hat model wasn’t chaos at all. It was a different way to run an organization that is more optimized for innovation than for driving efficiency. The book was like my lessons learned going from Delta where I thought, “That’s how you run a company, “and Delta does run an excellent company, to running Red Hat, which I would argue, is an excellently run company as well. But they look “night and day” because, in Delta, you don’t want someone innovating on the safety procedures before your flight. You want those locked down. You want people to follow orders.

At Red Hat, it is entirely about getting people to take the right smart risks and experiments to be able to innovate faster. The book says, “There are different ways to run depending on what your objective function is.” Most companies come from that old world. They’re trying to look like they are in the new world now but are not changing their ways of working appropriately to that.

You almost get this impedance mismatch between leaders saying, “I want my teams to be growthy and take risks.” They then have these management systems with these performance cadences, measurement systems, and incentive compensation systems that are all about driving variants out. One thing I would still like to do [with the book] is spend a little more time trying to flesh it out fully. I talked about the difference between Red Hat and Delta. I didn’t create a more systemic view of, “Here are the ten things to think about if you’re trying to make that transition.”

Maybe there will be a version two of the book, a second edition or a sequel…

Let’s go back to Delta. You were at BCG as a partner. Obviously, you were doing very well there. What led you to make the jump out of consulting? Were you actively looking to move from consulting or was it just a situation where they came to you and made the proposal?

I was very happy at BCG. Some of my best friends were in BCG. My wife was my office mate at BCG. I have deep roots in the firm. Delta had approached me many times. I had always said no but then 9/11 happened. I was down at Delta on 9/11 at noon. The CEO at the time, Leo Mullin, called me and said, “I need you now to be my treasurer. That job had happened to be open. The prior person had left.” I said, “Leo, I know nothing about being a treasurer.” He basically said, “That’s okay. Nobody in their right mind would loan us money. I just need somebody who can be creative and help.” I literally became treasurer of Delta at noon on 9/11.

Pick a role you can get passionate and excited about rather than what looks like the right logical next step, and then make it successful. If you're successful, new doors open. Share on XIt was a couple of things. One is that it felt patriotic at the time, I did have a lot of feelings for the senior team at Delta because I had worked with them for several years and had a real affinity there. We were pregnant at the time with twins. My wife was due in October, and this was September. The idea of coming into a place where I knew everyone well, they knew me well, and felt like a company that needed help at the time, but also then not having to travel as much, all came together. I joined as his treasurer. I did that for a couple of years. There was a new CEO in a transition, and the new CEO asked me to run the network, which [oversees flight operations], and then one year later to be COO.

It had strategy, operations, network, and all that stuff under it. Basically, I still can’t believe it. I was 35 at the time when he said, “We’re going to make you COO.” We knew we were hurtling towards bankruptcy, and we would probably have to fail in a few months. I was young and naive. I said, “Sure.” Knowing what I know now, it would be like, “Why would you ever take that job?” I didn’t know, so I did. It’s one of the greatest things that ever happened to me.

Even if you were there during a very difficult time, hurtling toward bankruptcy. I mean, [being] COO of Delta Airlines at age 35, it’s hard to argue with that, even if you are going to have to work through bankruptcy.

It was a phenomenal opportunity and a chance to get to do that. I thought I had a thesis of what we needed to do, so we put together the plan. I came back to the thesis but I didn’t think I had a sense of what we needed to do. I’m not sure I would have done it, but I had a good sense. We put together the plan and convinced the creditors’ committee that this was the right plan, and we raised a debtor-in-possession loan. We executed the plan, and luckily it worked. It was a phenomenal opportunity, and it was more fraught with risk than I was probably willing to admit to myself, but it was extraordinary to get an opportunity to do that and an incredible learning experience for me.

I remember there was an article that was talking about how you earned a reputation within the company, when you were out talking to employees all the time, for telling it straight while the company was going through a very difficult period, and you earned a lot of credibility with employees. Was that something that you feel like you are naturally good at or was it something that you had to work to develop?

I’m a little bit of a geek. I love strategy, and I like talking about it. Part of that comes naturally to me, and probably, I talk too much, but it was dumb luck. Right after the bankruptcy, I was asked to go over to a break room at the Atlanta Airport for the night shift mechanics. It was unplanned. I got there and didn’t have anybody who had scripted what I was going to say right after we filed. I got all these mechanics looking at me, thinking, “What am I going to say?” I started going through [the strategy] and saying, “Let me tell you the plan,” which is what we had been telling the creditors’ committee and the debtor in possession lenders and all those other people.

It was complex. It was moving wide bodies out of domestic to international and reconfiguring and down gauging. These mechanics were sitting there for 30 to 45 minutes. When I finished, they started asking intelligent questions like, “Our plane has the galley capacity to do that. Do we have the right number of wide body gates?” All these kinds of questions rather than, “How long before my medical benefits change?” It got around the airline very quickly – by the next day – that I had been there doing that. I started doing that [elsewhere]. I found that people wanted to know what they were a part of.

It’s one of the things I’ve talked about ever since and done at Red Hat. There’s a sense among many executives [to just say], “I know the strategy. I’m going to go tell you what to do,” [rather than] making sure everybody knows the strategy, so they know what they are a part of. That creates an intrinsic motivator. That’s huge. [We went] from last to first in on-time performance among the major carriers during the bankruptcy. It’s not like we had some brilliant change in operations. I’m totally convinced that it was because everybody knew the overall strategy of the company.

We’ve told people, “Being on time is how you can help us run a quality airline and get us out.” People went above and beyond. I called it, later on, “Flipping the pyramid.” Most people say, “The strategy can be ambiguous as long as you crisply understand your job.” I would flip it around and say, “If everybody crisply understands the strategy, let how they are doing their jobs be a little bit ambiguous,” so they have agency and control to shape it a bit and do what they think is best, because they probably know better than you do anyway.

That was a lesson I learned that was effective. I kept doing it, whether I was good at it or I learned to do it because of that – there was a little bit of both in there. I did that at Red Hat. I did a survey when I first got there. Most employees said they didn’t quite understand our strategy well. By the end of that year everyone did, and we’ve spent a lot of time laying it out, communicating it, and surveying that question every year. It’s important for people to be engaged to know what direction we are all rowing and why.

The “why” really matters. You can’t emphasize it enough. It’s more than the “what” and the “how”, explaining to people, “Why are we doing this?” If they can connect, connect what it means for them to the “why”, it makes it a lot easier for them to accept things, even when it’s maybe not personally great for them.

Delta was very simple. During the bankruptcy, we didn’t have time to go hire a consultant and do a big purpose study. We said, “We’re not going to let this fail on our watch.” Delta has been an iconic company in the South. A lot of people’s parents worked there and want their kids to work there. It was like, “We’re not going to let this thing fail.” That was enough. To build off of that, Red Hat opens and unlocks the world’s potential, this whole idea of open and sharing and how important that is. It’s incredible how strong, intrinsic motivators like that are, and how much people want to feel a part of something.

Thinking about your transition from Delta to Red Hat, you ultimately decided to leave Delta when they went in a different direction for CEO, which I was describing before we started the show as the ultimate bet in yourself – to walk out on a COO job where you’ve got 80,000 people working for you. How did you think about that at the time? Was it an easy or a hard decision?

Jim Whitehurst: When you’re the CEO and there’s no one behind you to make the tough calls, and the decisions you make can affect thousands of people’s lives, it’s different, even than being a COO or President.

The word “choice” might be a little strong. The way Delta was structured at the time, I was COO but almost all the major functions reported to me other than finance. When the new CEO came in, I got along with him. I’d known him for years. He had been running another airline. He basically said, “I can’t have one direct report. I’ve got to have the major functions.” There wasn’t a role for me. He said, “If you want to take any of the roles, pick one.” My role was going away. Honestly, I felt like I had been kicked in the gut. I was deeply involved in the day-to-day for two years through that bankruptcy.

I didn’t think about the other side. The creditors’ committee went with someone else, and there wasn’t a role for me. The decision for me on exiting was [between] three types of roles. One was to be very senior executive at another company – a big company – but not a CEO. A second was with private equity companies calling [me] to do turnarounds and the third was trying to find a smaller company CEO role.

I didn’t want to do another turnaround. We had to lay off so many people when I was at Delta, and it was painful. I had zero desire to turn around things [elsewhere]. I was really looking at the other two [options]. To get to the point, I had been close to number one for a long time, and I wanted to show that I could do it. Red Hat took a chance on me, given that I was an airline person going into technology. [The decision] was a little bit of that, and I thought I could do something [there]. Red Hat gave me the opportunity to do it.

It was a great situation to go into, given what we talked about earlier in terms of where they were in their evolution and the whole idea of open source and the movement that they were starting.

The lesson learned for me was that a lot of people, when I first did it, said, “You had 85,000 people working for a you. You could run big divisions and be next in line to be CEO of these big things.” Red Hat, at the time, was $400 million or $450 million in revenue and 1,500 people. It wasn’t that big. As my wife said after I talked to [Redhat], “I haven’t seen your eyes light up like that in a couple of years.” That’s why I knew it was right. It’s like, “Pick a role you can get passionate and excited about rather than what looks like the right logical next step, and then go make it successful.” If you’re successful, new doors open.

I want to come back and talk about the acquisition. When IBM approached Red Hat about the acquisition, how did you and the board work through that process?

I can’t talk about the board, but I can talk about me personally a bit in that. I got a call from [IBM CEO] Ginni [Rometty], who I knew. We had seen and done things [together] before. She said, “If you’re in New York on such-and-such week, let’s grab breakfast.” I said, “Great.” We got together. She slides a term sheet across the table. It’s one of those [cases] where you have to tease two things out of a situation like that: what’s best for you personally and [what’s best for] the company. Red Hat at the time was and still is very successful. Things were going well. When you’re a CEO who’s taken the company 10X in terms of revenue, market cap, etc., boards are generally pretty happy with you and let you run and do your thing.

Life was good. Everything was going along well. The idea of saying, “I’m going to sell and go work for another company,” I have to say, personally, wasn’t that appealing. No disrespect to IBM. When you look at where Red Hat was, which was selling open source infrastructure software in a world where public clouds give you open-source structure software for free to run on their public clouds, Red Hat’s standalone strategy was starting to feel like it was going to get tougher. We had always talked about, “We need scale to be the company that can abstract and run across these [areas],” but we were, even at that size with $4 billion [in revenue] – I didn’t feel like that was very big versus Amazon, Microsoft, and others.

IBM comes along with a very nice premium for the shareholders and the scale to try to make that strategy work. It was the right thing to do for shareholders and for Red Hat employees. Bluntly, it was tough for me. It took a while to get there mentally. The board very quickly realized the large premium. It’s not that we couldn’t have made it work but the probability of success of our strategy being part of IBM was much higher than standalone.

It was the right decision. We relatively quickly got to that, that we needed to be part of a bigger company. The board did because the premium was so big, so it was relatively easy. Frankly, the hard part was with a lot of the senior team. We’d built this thing, and all of a sudden, it was going to be a part of something else.

At some point, that’s where you have to decide you’ve got to do the right thing. Especially as a senior executive, you cannot let your own personal circumstances or preferences keep you from doing the right thing. It was the right thing to do. I’m from South Georgia. There’s a saying, “Says easy, does hard.” It’s easy to say, “Separate them” [what’s good for the company vs. what’s good for you personally], but it takes a while mentally to get your head there. It became very clear. It was the right strategic outcome. [I] finally got [myself] there. I had a great learning opportunity at IBM as well. So far, it’s worked out well.

Two very different cultures: high growth, innovative company, as you’ve described it, getting acquired by one of the biggest, oldest, most established tech companies in the world. How did you help bring those two together?

We did a couple of things. We talked a little bit about the book earlier and how I wish I had a little bit of a do-over. We started to get a lot more nuanced around how we thought about culture and ways of working. I gave a speech at Mobile World Congress a few years ago, where I basically talked about telcos going to see Google to learn about how they operate. I said, “Please don’t do that because, if the major telcos had Google’s ways of working, I would never be able to get a phone call completed again.” On the flip side, if Google had a telco way of working, we would see no innovation happening there. The issue is that most companies have some of both. IBM is a great example of that, running the world’s financial systems on mainframes.

You can't let your own personal circumstances or preferences keep you from doing the right thing. Share on XThere’s a reason that hasn’t moved to distributed architectures. These things have to stay up and run in any condition all the time and never fail. How you run to deliver that is the same way airlines run it in but it is a different way of working than in how you innovate. We started off saying, at least with Red Hat, “These are two cultures working together, not coming together.” We didn’t try to change the Red Hat culture. We very much said, “Red Hat needs to stay Red Hat and work with IBM.”

When I transitioned to the President role at IBM, we spent a lot of time trying to say, “We are [a unit] in the software group. How do we start to rethink that, given that IBM’s created mission-critical software for a long time?” As we were driving forward into AI and ML [Machine Learning] and some of these other categories, we asked, “How should we adopt some faster paced ways of learning lessons from the Red Hat model?” if you want to call it that.

Not to say that the Red Hat model is right and that IBM’s was wrong or not, because there are a lot of things, and I hate to even say [it’s just] innovation versus efficiency, but if you are trying to build a quantum computer, you need a whole set of work on microwave electronics to come together now, and the right refrigeration stuff two years from now to come together. That requires a level of planning.

If you are trying to drive a future state versus seek a future state, how you build management systems for that is different. Driving a future state could drive the variance out, but it could be that building a quantum computer requires that kind of level of precise planning. Whereas a lot of software is much more about seeking a future state, “How do I experiment and how do I try and work my way there?” If you think about those two extremes, IBM had both. Red Hat had one.

It is, how do you take components of IBM and say, “Let’s adopt more of this model?” Not because it’s better or worse. It’s just more optimized for a certain set of activities. I spent a lot of time teasing that out, getting crisper on that, and working with IBM to adopt more of that. It was a lot of my role while I was there.

How was it for you? You were CEO. You go to being President of a company that’s many times larger. What was that shift back into being, arguably the number two person there, similar to what you were at Delta?

The size, I didn’t find to be a problem. I had Delta, [which was big itself] and Red Hat, which had grown a lot. To be blunt, it was hard to go from being number 1 to number 2. I don’t think I have a big ego need. It sounded like I needed to be in control. As a matter of fact, I try really hard to be a participant in meetings, not perceived as the leader, because I get the best results that way. I have a great relationship with Arvind [Krishna, IBM’s current CEO]. He and I worked well together but psychologically, it’s hard not to say, “Here’s what I want to do. This is what we are going to go drive.”

I didn’t think it would be hard to step back from being number 1 to number 2. It is hard after you have been doing it [being the CEO] for a lot of years. The stress levels are a lot lower. Back to my point earlier, there is someone else behind the curtain that ultimately is the final arbiter. I found it less stressful but it was also a very different role to work, to execute, and I was engaged in strategy, strategy reported to me and all of that, but it’s a different role to be number 2 versus number 1.

It was a huge shock when you left in 2021. What are you up to? Everybody wants to know what Jim Whitehurst is up to post-IBM?

One of the things I realized after I decided for myself that I was going to leave IBM, but I had not yet told Arvind, was I spent a lot of time intellectually saying, “What do I want to do next?” What I’ve found, and maybe this is me, maybe others feel this way, is there’s only so much intellectualization you can do with that. At some point, you have to go live it. I finally decided, “I’m going to take a year off, experiment with a lot of things, see what I enjoy and see if I want to keep doing one of those more or jump back into being a CEO.” I’m doing several boards. I mentor a couple of younger CEOs, and I love doing that, working with them and working to make them successful.

I’ve gotten much more involved in several charities, where I have been able to take on bigger roles. Ironically, when you are a sitting CEO on boards, nobody makes you do that much work. You show up to the meetings and spout off a little bit. Now that I’m not a sitting CEO, I’m chairing committees and all these things, which I think is great to get to [do], whether it’s companies or nonprofits.

I’m much more involved with my university, and in some climate things. I’m spending some more time with my wife and travelling. When I left in July 2021, I said, “This July, I’m going to step up, reflect back and say, ‘Is there one of these things I want to do full-time or do I want to do the portfolio or other things?’”

I’m an advisor to Silver Lake, which I love. CEOs are notoriously bad investors because you have to be an optimist [to be a CEO], and you are the person out there trying to create a positive [message]. Good investors are more skeptics. I’ve loved engaging with the folks there. They are brilliant but think differently. It is wonderful to get to stretch a new set of muscles. I still have so much to learn and interesting people to meet. It’s lovely to have the privilege of being able to take the year and do that.

It is a nice thing. I’ve had a little bit of time off at points in my career. It gives you a lot of time to reflect and pursue some new hobbies and interests. I look back on those. In one case, in particular, it was stressful because I felt the pressure to find the next job. At the same time, I was getting to do things I was never going to get to do otherwise. That’s a blessing that not everybody necessarily gets.

I joined BCG out of college and went from there to business school and went back [to BCG]. Literally, at noon on 9/11, I showed up in the morning as a BCG person and in the afternoon [became] a Delta person. I never had a break there. The Delta to Red Hat [transition] was a relatively short time. It’s the first time I’ve had time off. I’ve had so many people tell me that, “If you ever have a chance between jobs to take some time, do it,” and I had never realized how nice it is to be able to do that.

I’ve read a dozen books. I’m doing photography. I’m spending more time talking to my kids, my mother, and friends that I had fallen a little bit out of touch with. Those are things where it’s hard to get that time back. I thought I would be more sitting on the beach, where I find myself very busy, but engaging with interesting people.

You got a lot of runway left if you want to dive back into something or a portfolio of somethings. What advice would you give people who are earlier in their career and trying to think about what they should do to learn as much as possible and help their careers as best they can?

First off, a lot of people try to act the part that they are in versus being themselves. If you are a good enough actor to be able to act a part, go to Hollywood and try to win an Oscar. I found that being able to say, “I don’t know. I would really like to learn that. I made this mistake,” is disarming for others. It builds your credibility with people because they are saying, “This person is comfortable enough with themselves to say they don’t know.” [Also], human beings interpret insincerity in very sinister ways. Insincerity is like, “I’m trying to act the part I feel like I need to play.” People look at that and say, “That doesn’t seem authentic to me. They must have an agenda,” versus, “Maybe they’re nervous or uncomfortable.”

Be yourself. Related to that, I ended up from Treasurer to running the network at Delta as a COO. They say, “How did the Treasurer get to do that.” A lot of it is curiosity. I went to lunch with the person who ran maintenance and grabbed coffee with the person who ran flight ops. Over time I was curious about how things worked. I talked to enough people that it almost kind of became, “Jim’s around. He knows a lot of this stuff because he has been around all the various areas,” where I had been in the company [only] a few years, but I had spent a lot of time being curious and learning more and more.

On the flip side is that it wasn’t like people didn’t want to have coffee. The guy who ran maintenance was saying, “What does a Treasurer do?” Those were good conversations to have. That curiosity matters a lot. The final thing I would say, and we talked about it before, is that when you have people working for you, thinking hard about creating the context for them to do their best work versus being so directive, you will get better people to work with you.

They will do better, which means you will do better. That’s probably the single biggest lesson I’ve learned. I go back to that night when I didn’t know what I was going to say to the mechanics at Delta. I spout off the corporate strategy. That was probably the most impactful night in my career that changed the way I thought about how to lead, and it made a huge difference.

You talked about reading books. Any books you want to recommend before we sign off?

I want to be careful not to get too far into my own industry, but I would definitely say if you haven’t read Flying Blind, that’s a book that came out about Boeing. I thought that was a phenomenal book, talking about how a culture can come apart with just a few years of leadership more focused on profits than on what’s the core of the company. Great companies are product-led. What I mean is they are built around, “What I am delivering?” You have to have great sales to go with it. Ultimately, you have a financial model but as soon as you get away from that core of what’s the product, that’s a problem.

Flying Blind, which came out in 2021, was a great one. I [also read] Empire of Pain. That’s a book about the Sacklers and Purdue Pharmaceuticals. It’s a great book. If you haven’t had a chance to read it, that would be high on my list. It may have come out in late 2020, but it’s a relatively new book. The Code Breaker, by Walter Isaacson, if you haven’t read that, it’s talking about cyber and the implications for cyber going forward. CRISPR, crypto, cybersecurity – three mega trends we should all know about. I haven’t read a good crypto book but I would throw those on.

If I could throw one more out there, How to Avoid a Climate Disaster, the Bill Gates book. I’m spending much more of my time philanthropically and professionally around areas about climate. That’s where I’ve gotten to the point of I have been fortunate and have some time to give back. I want my grandkids to be able to breathe. That would be my quick list of relatively recent books.

Jim, thank you. There’s so much more we could go into but I want to be respectful of your time. Thanks for making time. It was good to reconnect and catch up on things and know what’s going on with you.

This was great. Thanks so much for having me. I know you’ve had some great people on, so it’s an honor that you asked. I appreciate being here. I enjoyed the conversation.

I look forward to seeing you at some point soon if we are in New York.

It was great to have Jim as a guest. If you are ready to take control of your career, visit PathWise.io. If you would like more regular career insights, sign up on the website for the Pathwise newsletter and follow Pathwise on LinkedIn, Twitter and Facebook. Thanks and have a great day.

Important Links

- IBM

- TED Talk – What I learned from giving up everything I knew as a leader

- Santander Bank

- An Open Conversation With Jim – LinkedIn

- The Open Organization: Igniting Passion and Performance

- Flying Blind

- Empire of Pain

- The Code Breaker

- How to Avoid a Climate Disaster

- LinkedIn – PathWise

- Twitter – PathWise.io

- Facebook – PathWise.io

- Other PathWise podcasts

About Jim Whitehurst

Jim is currently a senior advisor to IBM and a special advisor to the private equity firm Silver Lake. He is also on the Board of Directors of United Airlines, cybersecurity firm Tanium, and digital optimization firm Amplitude, and he is an advisory board member for Santander Bank.

Jim is a regular speaker at corporate and industry events, has a TED Talk to his credit, and spent a year producing a management and leadership video series called “An Open Conversation with Jim.” He also wrote a book called The Open Organization: Igniting Passion and Purpose, which was published by the Harvard Business Review in 2015. Jim served as a member and vice-chairman of the North Carolina Economic Development Board and, in 2014, he was selected as the recipient of the NC State Park Scholarships program’s William C. Friday Award.

Jim is a graduate of Rice University, where he earned a Bachelor’s degree in Computer Science and Economics. During his undergraduate years, Jim spent time abroad at the University of Erlangan – Nuremburg in Germany and at the London School of Economics. He earned his MBA from Harvard Business School. He and his wife live in New York and have 2 children.