Yolanda Taylor – Investment Manager, Yoga Studio Owner, Author, Non-Profit Board Member

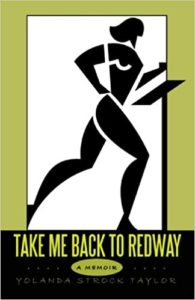

Career paths invariably take twists and turns – they are rarely linear. In this Career Sessions episode, J.R. Lowry introduces Yolanda Taylor, an Investment Manager, Small Business Owner, and Author of Take Me Back to Redway, the story of 8 years spent homeless in her childhood. Yolanda talks about the importance of hard work and determination. Even if you’re scared to take the next step, do it anyway. At the end of the day, your life and career are a series of short-term decisions. You may not get there on your first try or second. But you will! Just be confident in yourself and hang on to hope. Tune in!

—

Watch the episode here

Listen to the podcast here

Yolanda Taylor – Investment Manager, Yoga Studio Owner, Author, Non-Profit Board Member

On how a tumultuous childhood fueled her persistence, resilience, and belief in herself

I’m delighted to welcome Yolanda Taylor to whom I was introduced by our mutual friend and PathWise team member, Jennifer Velis. Yolanda is an investment professional, a small business owner, an author, and a passionate nonprofit supporter. Her investment career includes time with Fidelity Investments, Copper Rock Capital, Prio Wealth, and Putnam Investments.

As a small business owner, she has co-owned a power yoga studio in Lexington, Massachusetts for the past 10+ years. Her nonprofit work centers on children and women, including board roles over the years with Hope & Comfort, Cradles to Crayons, Compass for Kids, Parenting Resources Associates, and the Center for Women and Enterprise.

Her 2009 book Take Me Back to Redway covers her life growing up in poverty with her father in Northern California, ultimately before going on to the University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton School, where she earned her Bachelor’s degree, and to Duke University’s Fuqua School of Business, where she earned an MBA. Yolanda lives in Lexington, Massachusetts, and has four children. I am delighted to welcome her on the show.

—

Usually, I start off by asking guests about their first job. I find that question to be instructive about what people did when they were growing up. I know you had a difficult childhood, as you wrote about in your book. Let’s start there. Can you share a little bit about it? How has it shaped you as an adult?

I wrote a book, Take Me Back to Redway. It’s a back-and-forth story between my childhood and my present life. Present was at the time when I had given birth to our fourth child in four years and taken a break from my career. It was a back-and-forth story with the underlying theme of how do you instill in children the values of hard work and determination that came naturally to me as a child, given the circumstances that we lived in, against my present life. My present life was raising four young kids in essentially an upper-class household where that innate desire to want to go out on your own, make money, and be independent might not come as naturally.

My father was a reporter for the Associated Press and was assigned to cover the Vietnam War. That’s where I was born. I had a sister. My sister died at one. That, coupled with the turmoil of the war and everything that was going on, basically sent my mother into a depression. My father learned one day that while he was off at work, oftentimes like 15 to 18 hours a day, I was getting locked in a closet all day by myself. He panicked, so we left Vietnam and settled on the land in Northern California of all places. He had a couple of friends who had moved to that area from the war as well. We lived in Garberville, California, but Redway is the town that most people have heard of.

We spent four years living on the land of friends of his in a lean-to that he built. We spent four years living in a packing crate, one of those things that are attached to the back of a train that carries goods. It became dislodged from the train and [was lying] vacant on the side of the road. As hard as it might sound, [we were] living eight years on welfare, mostly outside.

I had a well-educated, loving single parent who was no longer working and devoted everything to my well-being and doing the best job he could as a parent. One of his main things was saying, “I believe in you. You can do anything you put your mind to.” That message was instilled in me from day one. The concepts of hard work and determination were my trademarks from a pretty early age.

That experience, I can’t even begin to imagine, but I’m sure it gave you a form of resilience that most people will never have to find.

It gave me a lot of perspective on parenting. That’s for sure as well.

It sounds like your father sacrificed a good chunk of his own life, devoting his time and attention to you.

It was a bit of a trade-off. As a journalist, you don’t make a lot of money, so most of his income would go towards childcare. Or [he could] not work, going on welfare and taking care of me. He chose the latter.

How old were you during that eight-year period?

I was aged 2 to 10. I don’t actively remember the first couple of years of it, but slowly I became aware that our situation was a little different. We ended up leaving California when I was ten and he decided, “I’ve got to get back in the workforce.” The job he got was in Hong Kong, writing as an editor for the South China Morning Post. We left the land of Hicksville, California, and moved to what was then the most densely populated city in the world, Causeway Bay, Hong Kong. It was quite different. I enrolled in a British school, full uniform, ruler on your fingers if you did something wrong, and very strict.

Even if you're trying to figure out things in life, write your thoughts down on a piece of paper. There's a lot of self-learning and value that comes from that. Share on XThat must have been a crazy transition for you going from essentially being homeschooled.

It was definitely a crazy transition. I didn’t appreciate it at that time, but from the perspective on what different lifestyles or areas can be like, I learned a lot. It was interesting too in Hong Kong because the school system was intense, primarily in Math and Science, and when I came back to the United States as a fourth-grader, I was so far ahead in Math and Science. It took a couple of years before I learned anything new, but I was so far behind in History and English. It all worked out in the end, but there were a lot of balancing factors going on.

Where did you live after that?

We lived for two years in Hong Kong. My dad met and married a Filipino woman who became my stepmother. One of his parents got ill, and he had grown up in upstate New York. We left Hong Kong. Whenever anyone asks, “Where are you from?” I always say upstate New York. I don’t go into the details of the earlier years.

We moved to upstate New York with my stepmother and then she had a child, my half-brother. We moved in with my grandparents and helped take care of them. I would say my life became fairly normal except for the fact that my abandoned real mother found us and got a big shot legal team [to sue for custody.] We were on the cover of the New York Times: “Vietnamese woman finds her daughter in upstate New York after ten years of searching the world.”

I spent essentially all of fifth grade in Family Court. Long story short, she lost full custody. She didn’t speak English at all. She was working multiple waitressing jobs in New York City. I was a happy, pretty well-settled kid now with a stepmother and a little brother as well. She got weekend visitation rates, turned them down, and I have never seen her again.

At that point, obviously, all of this strife in your first twelve years or so, things settled in a little bit more in your middle school, junior high years, and into high school.

It was normal. I was a runner and we ended up having a good running team. That ended up charting a lot of my path into college. I went to the University of Pennsylvania Wharton School of Business and ran track and cross country. No one in college even knew about my younger years. I was a recruited runner. Quite frankly, Penn and Cornell were the top two schools that were interested in having me run for them. I didn’t know anything about the Wharton School of Business, but when I got to Penn, I was like, “This seems cool. They’ve got this good business school.”

I liked the campus much more so than the rural Cornell type of campus. At that time, the advice of the coach was, “I’m not sure you have the grades to get into Wharton, but why don’t you apply to the Liberal Arts program? You can run here. If you do well, you can apply at the end of your freshman year.” I did well in my freshman year and I applied to Wharton. They have a dual degree program. I have a BA from Penn in Economics, and I have a BS from the Wharton School in Marketing.

When did you start to develop a sense of what you wanted to do professionally?

I fell into what I ended up doing professionally. There were two things. One is my father was a writer and I was fascinated by his work. When we moved back to upstate New York, he became a columnist for a paper, which meant he could write about whatever he wanted to. He was what I would call an investigative journalist.

He would [write about] the person who was wrongly imprisoned, do all sorts of interviews, publish tons of articles, and then the courts would rehear the case. I thought that was so interesting, but he said to me, “Don’t go into writing. It doesn’t pay any money. You’re going to live the same life I led and that you led as a kid.” As a kid, I was increasingly aware that we didn’t have money and had this burning desire to do better financially.

I got to Penn. I loved Economics. I decided that I wanted to go into Econ in some way. My Penn dream was to be the first female chair of the Federal Reserve. That was my dream. When I got out of Penn, I started applying for jobs my senior year. I interviewed at the Fed. I got the job, not as the chair, but as a junior low-level research associate earning something like $24,000.

I also interviewed for a couple of these “Wall Street jobs.” I interviewed at Cantor Fitzgerald, which I don’t know if you have heard, but it was on the 105th floor World Trade Center, one of the main companies that lost their entire staff on 9/11. I interviewed with Cantor Fitzgerald and I will never forget that day going to their offices.

I was there on a Friday on the trading floor. The unemployment number comes out and all the traders are screaming. The energy in the room is ridiculous, such a contrast between that and a cubicle at the Fed quietly doing research. The pay was something like triple what the offer was at the Fed. Here I am, the poor kid who went to Penn and had all of these loans, and I was like, “I’ve got to go the Wall Street route.” I ended up in New York on the 105th floor of the World Trade Center. I was in the first bombing in 1994 when they drove the truck into the basement. We walked down 105 flights, two and a half hours, a crazy memorable experience, needless to say.

When did you leave Cantor Fitzgerald?

I was dating my college boyfriend. He was down in the Atlanta area. I left about 1.5 or 2 years later, and I moved to Atlanta. The progression for me was that I was what you would call an intellectual at Penn. I loved economics research and getting into the details of things. I ended up on a Wall Street trading desk where you know the ticker.

You’re trading stocks and you know the 3-to-4-digit ticker [for the companies you’re trading] and that’s it. It’s unlikely you even know the name of the company, let alone what they do, who runs it, anything like that. Once [I got over] the excitement of that job, pretty quickly on, I had this itching like, “I need to know more. This is so high level.” I also wasn’t a huge fan of the whole element of greed and everything like that.

I moved to Atlanta to go one level up. Trading in New York City and then in Atlanta, I took an institutional sales job. My clients were the mutual funds in Boston. In there, now you know the ticker and the company name, so you know a little bit of information that the research analysts were doing on the companies. You’re conveying that information to the analysts and portfolio managers at mutual fund firms.

In that institutional sales job, I thought, “This is better. Now I know the company name and a little bit about what they are doing. These people I’m talking to, they’re going deep. They’re learning everything about the company.” I quickly realized, as an institutional salesperson, that in order to get to the next level of becoming an analyst or a portfolio manager for a mutual fund firm, I needed to go back to school.

I needed to get an MBA. I ended up applying to MBA programs and left Atlanta about another year and a half later. I spent three years working [following college] and then I went to Duke’s Fuqua School of Business School to get my MBA. I was laser-focused. I went to business school so that I could get a job [as a research analyst]. I had it in my mind right away. I was like, “I want a job at Fidelity.”

At that time, they were undoubtedly the best mutual fund firm in the business. I liked Boston. My coach in high school ran the Boston Marathon. We all went and watched. I remember thinking, “I want to go to Boston someday.” I was done with the New York City thing. Atlanta was nice, but I didn’t feel like there was enough going on for the stage of my career I was at.

There isn't one right path. Life gets in the way. Share on XI got a part-time job in business school as an analyst for a small money management firm in Durham, North Carolina. I started probably 3 or 4 months into business school calling Fidelity, anyone and everyone who would pick up the phone. This was the old days. All you did was call. You went to the library. You got these books and people’s phone numbers.

I called everyone that worked there and was like, “I want to work for you guys. Will you give me a chance? Can I come in for an interview?” Finally, I drove the recruiter bananas enough because Fidelity did not recruit at Duke. She was like, “Let me know if you’re ever in the Boston area.” Every week I would call. I would be like, “I’m going to be in Boston next week,” when, of course, I had no plans to be in Boston. Finally, she said, “Come on and we’ll meet with you.” It worked out. I got a job.

You worked hard to get yourself in the door at Fidelity. Once you were there, how did you find it? Was it what you expected? Was it similar or different?

I loved it. I was a summer intern. In my second year of business school, they offered me a full-time job and they gave me the opportunity to work part-time in my second year of business school. Every week, I would fly from North Carolina to Boston Thursday night, work Friday in the Boston office and fly back Friday night. That’s how much I liked it right from the get-go.

The thing that was fun for me was my point about the progression from being a trader to a salesperson. Now I was indeed going deep. The job was a combination of being good with people because you’re trying to form relationships with company management teams, get them to talk to you, and ask them questions. It also had that investigative journalism element to the job that was maybe my true passion from childhood. It was ever-changing.

I was an analyst on probably six different [industry] sectors during my tenure there. If you did well, you rotated from one sector to the next every year and a half. I rotated through a number of sectors as an analyst, from healthcare, and financials, to industrial companies, and then became a portfolio manager and then moved into management overseeing analysts. It was a great eleven-year run that I had. In my last couple of years at Fidelity, I had four kids in four years. I ended up making the pretty hard decision to step away. We had gone through a lot in having our kids, infertility, IVF, miscarriages, and all that stuff.

It had been a rough four years. Now, there I was all of a sudden. I ended up quitting when I was pregnant with my fourth. Our fourth child was not planned despite the fact that our first three children were medical miracles that we worked hard to get. There was something about this unplanned, natural pregnancy that felt like someone was telling me something like, “It’s time to take a break and step away.” That circled back to my father and the sacrifice he made for a while to be there for me. All that came together in not a day per se, but in a moment of all the thoughts and the conflicting feelings I was feeling. I left and became a stay-at-home mom for a while.

I know you got busy with nonprofit work. That was around the time when you wrote your book as well.

I left and things were busy at home, literally with four kids in four years. I had a lot of little ones, but we had some help. I left a little bit of time for myself. It was hard. I only ultimately ended up staying home full-time for two and a half years. I missed my career and that sense of identity. [I did] what I felt was right and what I needed to do, but I needed a challenge. I needed something that had tangible goals, even if self-created, like deadlines associated with them.

I needed emails to respond to and reasons to dress up and go to a meeting on occasion. I found all of that through writing the book and joining some nonprofit boards. They were linked to the audience of my book. It wasn’t deliberate per se, but I would say the target audience was single women who were raising children in a poor or homeless type environment and inspiring them [even though] things might be tough.

You might not be able to buy your kid designer jeans or whatever it is, but if you love your child and teach them that they can do whatever they can do, it’s okay. That was the message from my book. Partly because of that, I got involved in a couple of organizations that were centered around homelessness or helping single moms, families, or children in need in this area.

Yolanda Taylor: You might not be able to buy your kid designer jeans or whatever it is, but if you love your child and teach them that they can do whatever they can do, it’s okay.

It was fulfilling for a while. Certainly, writing a book was a decent undertaking. I took a class at GrubStreet in Boston, which was taught by a fantastic individual who ended up being my editor and encouraged me and helped me take it from start to finish. Through my nonprofit work, I got asked a number of times to be the keynote speaker at events and tell my story. I have gotten more involved in those causes.

Given what you said earlier, not sharing the early days of your childhood, the book was a coming out for you.

Writing it was therapeutic. My daughter is a writer and she struggles with anxiety issues. She writes poems and her whole heart comes out on that paper. They say, “If you are struggling, journal.” Journaling is a great thing to do. Even if you’re trying to figure out things in life, write your thoughts down on a piece of paper. There’s a lot of self-learning and value that comes from that.

For me, the book was my therapy and my project. It created the deadlines and goals that I needed, having stepped away from my career. It was also therapeutic to understand myself and the challenges I had gone through as a child and then the challenges I was trying to go on through at that time in terms of stepping off that career track to take care of my kids.

From a timing perspective, you were out of the workforce, formally speaking, while you were doing some of the nonprofit board work and raising your kids. When you went back, you started a yoga studio and went back into the money management business. Talk about the decision to do both of those things.

I was pretty fulfilled for a while. The book got done. I did some speaking. People read it. They gave me feedback. That all felt good for a while, and then I went through a period where I was like, “I did it. That’s done. Now what?” Raising kids is arguably the most amazing thing I have done in my entire life. I now have four teenagers. When they were little, for someone who is used to that corporate world, where you’re constantly getting feedback on things you do, whether it be your reviews, doing a good job, meeting a deadline…in parenting, the days are long, the years are short, or whatever some of these trite sayings are, but that sense of feedback isn’t there to the same degree.

You don’t know that the decisions you’re making and the things you’re doing, whether they’re ultimately going to translate into kids who are happy, become independent, are smart, and do well in school. You don’t know. You’re just doing what you’re doing, raising [your children]. I decided that I wanted to try to get back into the money management business. It was 2009, deep in the financial crisis. Fidelity and everybody else were laying people off. It was not a good time to think about wanting to go back into the business. It was interesting because, at that time, one of my jobs at Fidelity was as an analyst covering the investment banks and other large financial institutions.

I was doing the analytical work on these companies when they were clearly going down a bad path. I don’t want to say it was obvious because everyone missed it, but looking back, there were so many warning signs that the big banks were stepping out on that risk curve and taking on way too much risk. I remember being home when Lehman and Bear Stearns went bankrupt. Those were companies I knew well. I remember feeling, “I’m missing out on one of the greatest learning experiences that anyone could ever have working in this industry.”

It was, ironically, one of the things that made me want to go back because as hard as things like that are in the stock market, they’re also once-in-a-lifetime learning opportunities. I ended up getting a job at a relatively small institutional money manager to manage the healthcare portion of their assets. My longest stint, and the stint I loved most at Fidelity, was as a healthcare analyst.

This opportunity came up. It was fantastic. I would focus on healthcare, an area that I thought was interesting. I started at this company called Copper Rock Capital in 2009 or 2010. Fast-forward, they ended up going bankrupt four years later. Everything was great for a year and then it incrementally became not great. Clients started leaving. The writing increasingly became on the wall that this firm might not make it.

I was a bit stuck. It was a small firm. I was a partner. The client base was pretty concentrated. I didn’t want to be that person who left and created the domino effect. I was [living] in Lexington. I’d been a big runner in college and ran a lot after college competitively. After having my fourth child, I couldn’t go back to running how I used to. I used to a couple of marathons a year and all that. I saw a lot of people, physical therapists, chiropractors, masseuses, orthopedic surgeons, and all of that, and then I started doing yoga. I loved it. It worked and my body was feeling better.

The primary factor that makes people love their job is the people they work with. Share on XI’m in this job where things aren’t going well. I suddenly became addicted to yoga. The town laws in Lexington changed such that for the first time ever, businesses that offer group fitness were allowed to open in town center. Previously, you had Boston Sports Club on the edge of town, but there was nothing in the center. I was going to this yoga studio [elsewhere], and it was packed every single time. I started putting together a spreadsheet. I called the landlord of the building and the electric company.

I put together [a view of] their cost structure. I’m like, “I’m paying $15 a class.” There are 40 people on average in each class. It was not too hard to put together an expected income statement for the yoga studio I was going to. I’m like, “I can do this business. Why don’t I build this in Lexington?” It became almost similar to that time when I left Fidelity in the first place and decided to write a book. It became my challenge while I felt stuck in a finance job that had a limited lifespan.

It was interesting. I spent maybe a year looking at real estate, meeting with the various town people you have to meet with to get permitting, and things of that nature. I was due to sign the lease, say, on a Wednesday. I was leaving for France right after I was due to sign a lease. On Tuesday night, the night before, someone called me and said, “That’s weird. I thought you told me you were going to open a yoga studio, but I heard of the yoga studio is opening up in a different location right in town.” I was like, “It must be me you are talking about. It can’t be someone else.” I paused and the next morning, I called around and it turned out there was another person looking to do the exact same thing in Lexington that I was.

I found out who this person was. I called her, and I said, “I found out you’re looking to do the exact same thing I am. We’re either both going to do this independently and there’s no way the town is going to support two yoga studios, or we can join forces.” We agreed to meet. We hit it off and we became partners. I took the space she had signed on. I let go of the other space I was looking at. She had a better location. Several years later, we now have three studios. It has been a great lasting partnership.

That’s great, considering that you didn’t even know each other beforehand, that it has worked out as well as it has. That’s rare. How did the two of you complement each other?

I brought the financial side to the equation, not that analyzing stocks is necessarily the same as bookkeeping for small businesses. She had an operations background. Those were the two main complements and then we figured out marketing. The reality of a small business is you do everything. I have many memories of cleaning dirty toilets, the roof caving in, and running to the studio in the middle of the night because there was a big leak.

I learned a lot. It’s night and day from a large organization or even a small organization where you call somebody when your computer does not work. In a small business, you have to do everything yourself. There is nobody to call. There’s you. At the same time, there are not fifteen meetings to come to a decision on anything.

You talk it out, send a couple of emails to each other, and say, “Let’s give it a try. Let’s do this and that.” I often ask people when I interview them, “What do you prefer? Big company, small company, or medium-sized company?” It depends on the situation and it depends on who you work most directly with.

A friend of mine got her PhD in Organizational Behavior. Her dissertation was on what are the primary factors that make people love their job. The number one factor was the people you work with. You can do stuff you’re not interested in, but if you like the people you’re working with, everything else will be fine. For me, that has proven true very much so with the yoga studio. I love my partner. We have a third partner as well. We trust each other and we’re friends for life. That goes a long way in terms of what you choose to do.

You eventually again went back into money management. I know you were at Putnam until recently. You’ve made a decision to leave that world again. Now you’re at another crossroads.

I am, which feels in some ways frustrating but also enlightening. At the moment, you always do what you think is right and what you need to do. If I have learned anything all these years, it’s that there isn’t one right path and life gets in the way. You have to work around that. I got an opportunity to join Putnam. Someone I had worked with for quite a long time at Fidelity.

Yolanda Taylor: With parenting, you don’t know whether the decisions you’re making and things you’re doing are ultimately going to translate into kids who are happy, independent, smart, and do well in school. You don’t get feedback in the way you do in a work setting.

I was building out their sustainable investing practice, which is a fantastic, relatively new area of investing that has gained a lot of traction and has influenced a lot of what we’re seeing in terms of how corporations are organizing themselves. It’s interesting even to teenage kids. My son will only buy sustainable products now.

It doesn’t matter what he’s buying, a new T-shirt or anything, but he cares about that stuff. This young generation cares about that stuff. I would argue that a lot of this came from the investment community pushing companies to care about things other than just short-term profits. Now the government has gotten involved.

It [working at Putnam] was great, but I have two juniors, a freshman in high school, and an eighth-grader. My two juniors, the one is my daughter with anxiety issues, they’re starting the college search process. There’s a lot going on right now, so I needed to step away.

I’ve chosen to step away. I’m still actively involved in the yoga studio. I put most of my time into one nonprofit that I’m a part of, which ironically was founded by one of my best friends who retired from Fidelity. Hope & Comfort distributes toiletry and hygiene items to those in need in Massachusetts. I basically split my time between both of those.

Will I go back to the investment business at some point? I don’t know how much longer I will work. A lot of [what matters now] are my own individual passions and areas of interest, and I’m passionate about giving back and helping people who need help in Massachusetts. Obviously, that’s my nonprofit area. I’m passionate about wellness and fitness. In addition to the yoga studio, I have done two Ironmans in the last couple of years.

I do a decent amount of endurance fitness events. I’m training for a five-day climb of the major peaks of the Tour de France in July. This was a bucket list when I left Putnam. There is so much going on, and I was like, “I need something.” You always need something. That’s one of my big goals right now to do that. I’ll do that and help my kids get their college applications in.

Hopefully, they can both get in early decision. We’ll have those done by November 1st, they’ll know shortly thereafter, and then we’ll figure it out. That’s my plan right now, but I know there is something else. I just don’t know what it is. I want to be careful, smart, and thoughtful about what that is, and if there is a way to combine some of my personal passions with work in a more specific way. I did that a bit with the yoga studio, and then I’m all in.

When you get those chances to combine your profession and your passion, it’s a nice thing. I know you know listened to my interview with Andrew Messick from Ironman. He got to do that. It took his wife telling him he needed to go take that first job with the NBA. He left for the sports management world and off he went from there.

I know that episode. It was inspirational to me. I love that you said you’re an endurance athlete yourself. I love that world.

I have a lot of respect for people in that world. His story resonates with me.

There’s a special mindset of people who like pushing it to the limit athletically. In a lot of cases, myself included, there is something from your childhood. There is an inner drive that got created at some point that [allows you to be] okay with pain and enjoy it. I don’t know what’s next. I’m definitely at a transition point. Our good mutual friend said to me, “Don’t do anything for six months.” I’m trying not to do anything new for six months.

At the end of the day, your career and life are a series of short-term decisions that lead to that resume that you put together. Share on XGiven that your attention right now is in part on your two juniors and getting them through the college application process, not taking on too much in the next six months is probably good advice.

It’s easier said than done.

I’ve sensed from you that there is a strong inner drive that’s fueled you all the way through. Going back to your childhood, to however many times you called Fidelity, trying to get yourself in the door there, and then things went from there. What advice would you offer to people who are contemplating how to manage their careers best?

It’s what I was saying in terms of there is no one right path. When I originally left Fidelity and stepped away from what, at that time, was a clear and obvious path that I was on, I was so scared I would never get back in and no one would hire me again. That’s not true. Smart people who have a lot to offer, hard workers, personable [people], or whatever it is. Different careers demand different things. There will always be opportunities. What is hard and hard for me right now is, on a given day, it might not be clear or obvious at all what those opportunities are going to be, but there’s no one path or right way. There’s no roadmap to how you’re supposed to do this.

Your career and your life are, at the end of the day, a series of short-term decisions that lead to the resume that you put together. It takes a degree of self-confidence and hanging onto hope. If you’re looking to make a transition, it might not be on the 1st try, may not be on the 2nd try, but you will get there where you can feel fulfilled. One of my favorite words is action. If you do something you’re passionate about, it’s fun. That’s where I will be. I’m going to be confident in that.

It takes patience, faith, and at times, hustle and perseverance. For everybody, it’s different. There is no one path. Even these moments of career transition are unique for different people. You have to trust that you will figure your way through it. On that note, why don’t we wrap up? I know you have to go. This has been a great conversation. It was nice getting to know you. I appreciate your time. Have a good rest of your day, Yolanda.

Thank you so much. Have a good one.

Take care.

Important Links

- Hope & Comfort

- Center for Women and Enterprise

- Take Me Back to Redway

- GrubStreet

- Andrew Messick – Previous episode

About Yolanda Taylor